![]()

Iraj Qaderi Azar, known by his artistic pseudonym Zhilemo, has travelled with a trove of dozens of paintings and sketches from Mahabad – once the capital of the Republic of Kurdistan, a country established in 1946 in northwestern Iran – to Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI).

Over the years, surrounding nations and superpowers have stolen as much of Kurdish sovereignty and achievements as they could, or at least distorted or obscured them. Referring to his nation’s shrouded history, Zhilmo’s mission is clear: “I want to breathe new life into Kurdish history.”

Zhilemo spent his childhood years outside of Kurdistan, making him unfamiliar with his homeland’s language, culture, and art. After completing his university education, he found himself employed as a petrochemical engineer at a refinery in Isfahan, the historic capital of the Safavid Empire.

“Once, I decided to familiarize myself with the written Kurdish language. I carried the poetry collection Naley Judai by Kurdish poet Hemin Mukriyani with me to Isfahan, and I must admit, reading the poems was a difficult challenge,” he recounted. “However, I refused to give up. Having already delved into the works of classical Persian poets such as Hafiz, Saadi, and Firdawsi, I recognized the importance of acquainting myself with my native language and culture.”

“I have spoken Kurdish since I was a child,” he continued, taking a deep breath. "But it was difficult for me to read in Kurdish. I worked hard and learned to read Kurdish by reading Hemin's poems. Within Hemin's literary works, there resides a treasure trove of Kurdish tales and folklore, many of which I had no prior knowledge of,” Zhilemo observed.

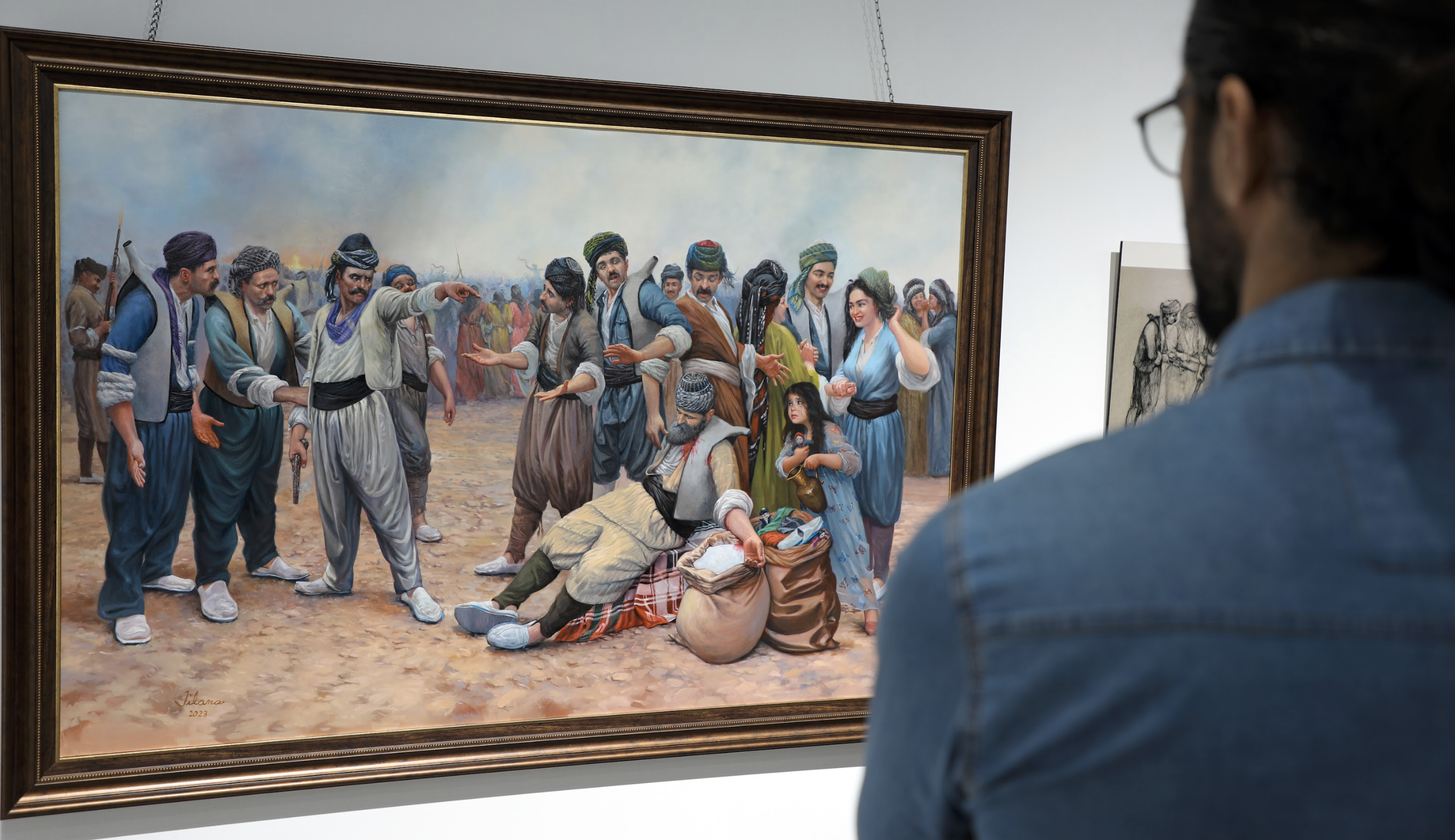

Exploring one’s hidden cultural heritage can be a deeply emotional journey, a sentiment colourfully reflected during the Dimdim Castle exhibition hosted at the Media Hall in Erbil. The event, which was sponsored by Mam u Zeen Cultural Center and Kurdistan Chronicle, showcased a collection of paintings and graphic works by Zhilemo.

As visitors looked upon his art, they were invited to turn the pages of the book of Zhilemo’s life and dive into his emotions. When confronted with the culture of his homeland, words failed him. In that emotional moment, he couldn’t help but reflect on his nation’s bitter and plundered history, and how painful it is to be separated from one’s roots.

Zhilemo explained, “Hemin’s book of poems served as my inspiration to seek out the richness of Kurdish history and culture. It was as if I had been living in an isolated desert, ignorant of the cultural wealth that surrounded me.”

“Do you aim to compensate for your alienation from your nation’s culture through art?” I asked.

He seemed pleased with the question, responding with conviction. “I want to breathe life into the Kurdish past, rekindling the fire of a history that lies hidden beneath the ashes.”

Engaging with our roots

Many Kurdish artists believe they should not be cut off from global artistic trends. As a result, they find themselves surfing the waves of globalization, engaging in debates about modernity and postmodernism, all in an attempt to align with changing trends. This kind of artistic journey is characterized by a steady influx of influences from the West to the East throughout the 20th century, which has continued well into the third millennium.

However, Zhilamo believes that this way of engaging with the art world obscures the work itself. “I believe that returning to one’s self, to one’s heritage, is the origin of art. As member of a Kurdish nation, we need to become acquainted with our identity more than any other nation, and through this engagement with our roots, we need to introduce a beautiful and static discourse to our nations, near and far.”

The exhibition featured a series of graphic sketches and dozens of oil paintings, creating an atmosphere within the Media Hall that pulsated with vibrant colors and dynamic shapes. The exhibition resonated so much with the feelings of Erbil residents that the exhibition hall saw a steady flow of visitors all week, with some staying for more than two hours. People find it fascinating to read the pages of a nation’s history through the art of painting and witness stories of love and heroism in color and shape, so the exhibition was a flying success.

“I don’t follow any specific art style, and I haven’t pursued formal academic studies in art,” Zhilamo explained. “For the past five years, I’ve been immersed in the world of professional painting. I began by reading art books, but I soon realized that they were limiting my creativity. Yes, they provide valuable insights into painting techniques and art principles, but I had the impression that these books were unintentionally nudging my artistic inclinations in an undesired direction.”

“I’ve returned to my artistic roots. I’ll let my hands, fingers, brushes, and paint hang together,” Zhilamo confidently stated. “What you see is the end result. In each of these works I have given my 100% in all aspects: ideas, techniques, figures, sketches, composition, color, shape, and harmony. No matter what I do, the gender balance does not always reach the level I want. In some paintings, one gender receives higher marks than the other. I can feel the flaws, or rather the imperfections, in each painting, but I can’t push any further than I have,” he concluded.

The story of Dimdim

The exhibition bore the title Dimdim Castle, a poignant reference to a historical symbol of Kurdish resistance in the quest for freedom and independence. This historical episode unfolded in the early 16th century when a Kurdish emir named Amir Khan Lepzerin wished to establish a great state for the Kurds, thereby liberating his people from the rule of the Safavid and Ottoman empires.

In pursuit of his vision, Amir Khan set about restoring Dimdim Castle, an ancient Sasanian fortress located west of Lake Urmia. Within the fortress, he built a formidable council, palaces, buildings, markets, and streets. When the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas learned of Amir Khan’s ambitions, he dispatched an army to crush the ruler’s dreams.

However, in an initial clash, Shah Abbas’s forces faced defeat at the hands of Amir Khan's determined warriors. In response, Shah Abbas himself led a substantial army to besiege Dimdim Castle for a gruelling three months. Despite their dire circumstances, he was unable to conquer it.

During the siege, Shah Abbas’ forces discovered a vital source of drinking water for the fortress, which had been hidden underground and emerged from a nearby mountain. To break the spirit of Amir Khan and his valiant warriors, Shah Abbas cut off the supply. Indeed, the warriors’ resistance gradually dwindled, and when Shah Abbas’ army finally broke through the castle’s defences, not a single Kurdish warrior surrendered. Instead, they fought with unwavering heroism, remaining firm until the end. The battle concluded with the tragic death of Amir Khan.

The story of Dimdim is an example of resistance against the superpowers that have risen around Kurdistan and attacked the Kurdish homeland. The tale inspired both the title of Zhilemo's exhibition and the largest painting in it. Zhilemo tells the story of the Battle of Dimdim in great detail in this painting, a story unparalleled in the history of many nations.

The artist has referenced many other Kurdish stories in this exhibition, some of which are love stories, a popular genre among Kurdish writers.

One of the paintings that garnered significant attention from exhibition-goers depicted the legendary Kurdish leader, Mustafa Barzani, and his heroic fighters as they crossed the Aras River into the Soviet Union in the wake of the fall of the Republic of Kurdistan in 1946. Following the dissolution of the Republic, Barzani and his fighters engaged in a fierce three-month-long battle against the Shah of Iran’s forces before retreating from Iranian Kurdistan to Iraqi Kurdistan. Amid the looming threat of attack from the UK’s Royal Air Force and the armies of Iran, Iraq, and Turkey, Barzani and his steadfast companions adamantly refused to surrender.

Against all odds, Barzani and his companions embarked on a 32-day march to the Soviet Union. Just as Amir Khan Lepzerin and his warriors had refused to yield, Mustafa Barzani and his comrades stood their ground. Although this decision put the 500 Kurdish fighters led by Mustafa Barzani in the crosshairs of the armies of three states, neither Barzani nor his fighters were afraid. Instead, Barzani had his warriors cross the Aras River, finally crossing himself once they had made it. The story of crossing the Aras is depicted beautifully in Zhilemo’s painting.

The artist keeps his word, rekindling his country’s history, to illuminate it in motionless language.

Tariq Karezi is a prolific Kurdish writer, translator, and journalist whose career started in the early 1980s. He has authored and translated numerous books, and his influence is felt through his work in over 20 Kurdish and Arabic newspapers. He has contributed to more than 120 publications with articles mainly on culture, history, language, and literature.